SPURN PUBS: A History by Jan Crowther

How far can we go back? To Wilgils? Wilgils was a hermit who lived on an earlier peninsula in the 7th century. As an ascetic living a solitary life devoted to prayer he cannot play much part in this story. To the little borough of Ravenser Odd which stood on an earlier peninsula in the 13th century? The origins of the town seem apt – ‘about the year 1235 by the action of the sea, sand and stones accumulated at the tip of the Spurn peninsula, and on this land men began first to dry their nets and then to live. A ship was wrecked on the headland, and an entrepreneur made himself a hut out of the wreck and “received there, sailors and merchants, and sold them meat and drink, and afterwards others began to live there”’ (Barbara English, The Lords of Holderness, 1086-1260). Are these Spurn’s first recorded hostelries? I think so! The town began to grow, and over a period of a century gained a Royal Charter, two Members of Parliament, a market, a fair, a mayor, wharves and warehouses, a windmill, tanneries, and of course alehouses. Its story is a romantic one, but ultimately tragic. The sea won, as it always does on the Holderness coast. By 1346 the houses and land were being destroyed by the waves. The area became an island (history repeats itself!) and between 1356 and 1367 Ravenser Odd was completely destroyed.

In the centuries that followed, the peninsula changed, grew, diminished, grew again, but remained a very quiet place. Henry of Lancaster landed on the peninsula in 1399 on his way to claim the English throne. He was met by Matthew Danthorpe, a hermit who’d made a home there. In 1427 another hermit, Robert Reedbarrow, was granted a licence to build a lighthouse, but it is uncertain if he actually did so. When Edward IV landed on what was now called Ravenser Spurn or Ravenspurn in 1471 there was no mention of a lighthouse. It was in the 17th century that what we think was the first lighthouse was erected by Justinian Angell, beginning a long and complex story of lighthouse building on the peninsula. Trust me – there is a link with alehouses!

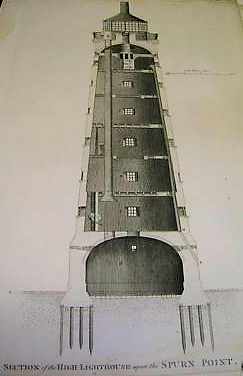

The lighthouses were owned by the Angell family, though from the 18th century they were actually under the management of Hull Trinity House, which appointed the keepers and inspected them regularly. The keepers were generally local men and most of them stayed for many years. Manning the lighthouses did not take up all their time and, in the 18th and early 19th centuries, they ran licensed premises to supply both residents and visitors to the Point with liquor. The first recorded licensee, Patrick Newmarch, was the lighthouse-keeper from 1736 to 1767. He applied for a licence to run a public house every year from at least 1754, and probably before. Visiting ships apparently furnished him with most of his business, and when he lacked customers he seems to have been an enthusiastic partaker of his own liquor. In 1765 Newmarch was replaced as keeper by Audas Milner, who applied for a licence to sell liquor himself, though Newmarch remained for another two years, still running his own hostelry. By this time the low and high lighthouses was becoming increasingly decrepit, inefficient and badly sited. This is when the celebrated civil engineer, John Smeaton, came to Spurn.

John Smeaton’s plans for high lighthouse at Spurn

The building of new lighthouses, from 1767 to 1776, designed by John Smeaton, brought many strangers to Spurn. William Taylor, the contractor, leased a house, which had been originally built for shipwrecked seamen, and applied in his turn for a licence to sell liquor. In 1771 Angell's agent, Worth, brought ‘a gang of unruly labourers to Spurn, [and] kept them well supplied with liquor’. By that time Taylor's rival licensee was another lighthouse-keeper, John Foster, with whom he was constantly at odds. On one occasion Foster was alleged to have thrown burning coals (presumably those used to keep the light burning) over one of Taylor's workmen. Workmen were very difficult to keep in such a remote place, and the easy availability of liquor from two hostelries caused extra problems. Smeaton wrote in 1774 ‘I believe that after they have once got drunk at the light housekeeper's they seldom go to work any more.’ Foster was dismissed in November of that year, but Taylor remained on Spurn, continuing to run a licensed public house, until at least 1780. Records show that between 1780 and 1788 there were no less than three licensed hostelries on Spurn, though their names, if they had any, are not recorded. One pub, which was recorded on the Point from the 1820s to the 1840s was the Tiger, which in the 1841 census John Thompson was described as running in conjunction with his lighthouse duties. Thompson was the last keeper to combine the job of licensee with that of lighthouse-keeper.

Spurn was to become a busier place in the 19th century, beginning during the French Wars when signal stations were set up on the Point in 1796 and 1803, and a barracks was built there in 1804. One assumes that plenty of strong drink was quaffed during these years but we know of no actual inn until the arrival of a lifeboat and crew in 1810. This was the initiative of the Constable family of Burton Constable. The number of ships wrecked off Spurn, especially on the Stoney Binks, was staggering. It was apparent that a permanent lifeboat was needed.

By agreement with Francis Constable – ‘the lifeboat master was to have a residence fitted up, management of the public house, and to be supplied with coals, candles, a spy-glass, a flag staff and flag and six casks for the storing of fresh water. For these supplies and concessions, £47 10s. 0d. was to be deducted from the master's earnings per year, and should his earnings not reach £100 per year, then they were to be made up to that figure by Mr. Constable’. By 15 August 1810 Robert Richardson had been appointed the first lifeboat master, and the new lifeboat arrived in Hull on 2 October of the same year. The house he and his family occupied is probably one of those between the low and high lighthouses shown in this print. Richardson’s crew at first travelled from Kilnsea and Easington when called out. For obvious reasons, that did not work and cottages were built for them in 1818.

The low and high lighthouses, 1829, looking south-west

In 1835 George Head, writer and traveller, visited Spurn. He described the landlord of the inn as ‘aguish and rheumatic, eatables were scarce, [but he] had in store abundance of liquid refreshment; [though] all I required was a feed of oats for the animal I had ridden, and of these there were none’, and the landlady, who ‘produced a good collection of agates, and other fine pebbles, picked up on the adjacent shore’. Head may be describing the Tiger, run by John Thompson, lighthouse keeper, who a few years earlier had been described as elderly and infirm. Richardson, the coxswain, was 55 when Head visited, and served another five years, so one hopes he was not plagued with rheumatics whilst carrying out such a strenuous job as lifeboat coxswain! The coxswain’s pub was usually called the Life Boat Inn, or the Lifeboat Hotel, a name that it retained after it moved into the first cottages on the Humber side (see below). In the early years there seems to have been no lack of business, for the labourers at the gravel trade were thirsty souls who were given an allowance of 6d. per day that had to be spent at the inns. The Lifeboat Inn’s beer was two-pence half-penny a pint, whereas the Tiger’s beer was only two pence, though of apparently inferior quality. Constable’s agent advised Richardson to lower the quality of his beer as ‘the labourers at Spurn are no judge of quality and their heads and stomachs can bear anything’.

When Robert Richardson retired in 1841 he was replaced by Joseph Davey, who lost no time in placing the following advertisement in the Hull Advertiser – ‘Joseph Davey begs to inform Masters of Vessels and other, that having been appointed Master of the Life-Boat at Spurn Point, he has entered upon the Public House lately occupied by Mr. Richardson, where he intends to keep a choice Stock of Spirits, Wine, Ale, Bottled Porter, etc. all kinds of Groceries, Bread, first and seconds Flour, and Salt Provisions in Casks and by retail’.

Under Davey's management the Spurn station declined in efficiency, and he was replaced in 1843 by Robert Brown, who entered into the trade of licensee with enthusiasm, putting a similar advertisement in the Advertiser. However, he found that the decline in the gravel trade as a result of the new regulations had led to a considerable loss of income, and he wrote to Trinity House in 1846 that he wished to ‘erect a Tenement for the accommodation of visitors, a considerable number of whom have been down, and across the Humber from Cleethorpes, during the late summer, but for whom we have no accommodation’. Brown obtained permission from Sir Clifford Constable, the owner of Spurn, to erect such a building but, only two years later, having been refused an outdoor licence, he resigned, asserting that he could not make a living unless allowed to take beer and other drinks out onto the beach. Apparently visiting parties such as that of Captain Bell of the pilot ship Neptune, who, in 1846, gave ‘a select party’ a trip to Spurn and back, were not enough to make a living. Brown was succeeded as coxswain and innkeeper by Michael Welbourn, who remained in the post until his death in 1853.

In 1858 a writer, Walter White, visited Kilnsea and Spurn. This was at the time that a new row of cottages for the lifeboat crew were being built, on the site of what became the car park. White observed that - 'beyond, them, towards the point, stands a public-house, in what seems a dangerous situation, close to the water. There was once a garden between it and the sea; now the spray dashes into the rear of the house; for the wall and one-half of the hindermost room have disappeared along with the garden, and the hostess contents herself with the rooms in front, fondly hoping they will last her time.’ This landlady was probably Mary Ann Tennison, who certainly ran the pub in 1861, and may have run it earlier. She was the unmarried daughter of Edward Tennison who had run a beerhouse in Kilnsea, and the sister of Medforth Tennison who ran the Crown and Anchor. Family connections between the licensees of the various pubs is a constant pattern at Spurn and Kilnsea in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Clearly the pub in the former barracks was on borrowed time and when the row of 10 new houses was ready for the lifeboat crew the pub was moved into part of the original cottages. The one nearest the Humber was renovated and extended to become a two-storey building incorporated in the row of 1819 cottages. The original name, the Lifeboat Inn or Lifeboat Hotel was retained. The pub now was no longer the province of the coxswain. A directory of 1872 shows Thomas Quinton at the Lifeboat Inn, but from the later 1870s James Hopper was the inn-keeper. He was a son of Fewson Hopper, a lifeboat-man from 1857, and promoted coxswain from 1865-77. James remained as the licensee until just before the First World War.

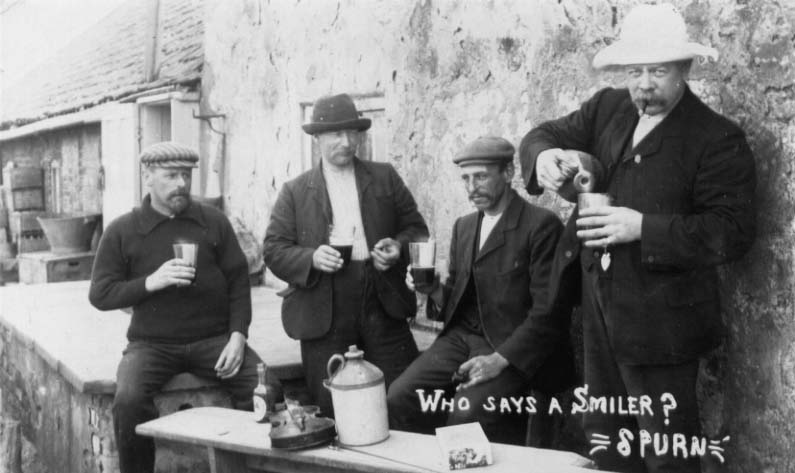

In 1878 Richard Stead visited Spurn, observing a little colony comprising: the lighthouses, coastguards' houses, life-boat house with the dwellings of the crew, post office and telegraph station, some fishermen's' cottages, and last, but certainly not least, the inevitable "public". To this last we went in search of refreshment, which by this time we began to feel the want of. We found we could have some ham-rashers and some home-grown potatoes. "What! potatoes grown here," we said, somewhat amazed, and looking round for indications of anything like garden soil; "Where do they grow?" "ower there i' them gardens," said the landlord, pointing to some rough railings a couple of hundred yards away. "What in the sand?" we asked, being not satisfied. "Aye, and good uns they are," he replied.

They were offered for drinks "Ommost onny mottle thing", and learnt that the average sale per week during summer was from 60 to 100 gallons of draught beer, 40 dozen of bottled beer, 30 or 40 dozen of soda water, lemonade, &c, besides other things in no small quantities. This consumption was explained by the numerous visitors to Spurn by boat in the season. The public house was a popular venue with the people who came in steamers in the summer months, whilst for those who did not wish for alcoholic refreshment the wives of the lifeboat crew offered tea and food. Lifeboat families running cafés on the Point is by no means a modern phenomenon!

Thirsty customers for the Lifeboat Inn disembarking from paddle steamer

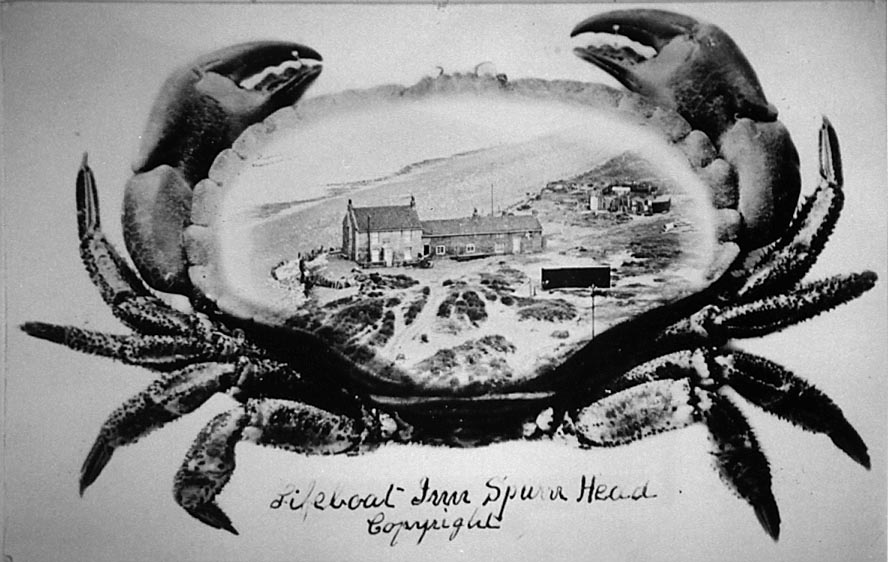

James Hopper, the innkeeper of the Lifeboat Inn was also school manager and kept a close eye on the school, which was attended by his own children. He was to be the landlord of the Lifeboat Inn for almost 40 years. Because of a wonderful collection of photos in the possession of the Hopper family we have some great photos of the Lifeboat Inn and the people who ran it and its customers. In the 30 years James Hopper was to remain as landlord of the Life Boat Inn, he and his wife raised a large family there, and provided a home for his sister, Eliza. She was the postmistress and for a short time also the schoolmistress of the little school on the Point, which was established in 1891. Numerous postcards were printed at this time for the visitors, and some of them showed the Lifeboat Inn.

Crab with Lifeboat Inn

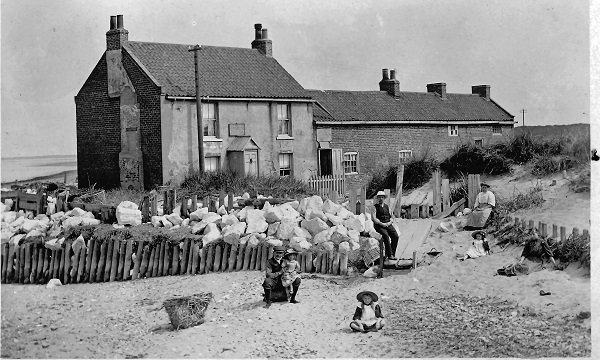

Lifeboat Inn and members of the Hopper family, c. 1900

View of Lifeboat Inn from the Humber, c. 1900 (note shoring up to protect building)

Rear view of Lifeboat Inn, c. 1900

Picnic behind Lifeboat Inn, c. 1900

Customers, chickens and dog outside Lifeboat Inn, c. 1900

Customers outside Lifeboat Inn, c. 1900

A painting of the Lifeboat Inn, from an autograph album belonging to Lily Hopper

Then as now, alfresco meals in the summer months were popular on Spurn. And in the early years of the 20th century little huts (or even converted boats) can be seen in those early photos, presumably erected as little holiday homes. Customers for the pub! On a more sophisticated level was Dr William Henry Coates of Bleak House in Patrington in 1891. He was a magistrate, general practitioner, county councillor and local benefactor, with a partiality for the arts. He soon discovered the pleasures of Spurn and Kilnsea, and had a sort of beach hut (which he called ‘Our Flat’) built in the dunes, where he entertained visitors, many of them ‘theatricals’ from Hull and further afield. Not a pub exactly, but certainly a place dispensing drink, though the photo below seems to show afternoon tea!

Dr William Coates and visitors in ‘Our Flat’

When Warren Cottage became vacant about 1908, Dr Coates rented it to use as a pied-à-terre. In the early years he visited by horse and trap, and when he bought a car he was probably the first person to motor to Kilnsea. His visitors made regular treks down to the little community on the Point, and entertained the locals and visitors. Lily Hopper, the daughter of James Hopper, licensee of the Lifeboat Inn, recollected that whenever the family visited Hull, they had the very best seats at the Hull theatres.

Not to over-romanticise, but Spurn before the Great War, especially in the summer months, must have been a wonderful place. Accessed more easily by water than land, because at that time there was only a rough track down the peninsula, nevertheless it seems to have been a busy place and a good living for James Hopper and his family.

Everything changed in 1914. The government decided that the defence of the Humber and Hull and inland required a military fort on Spurn and another in Kilnsea, linked by a railway. Spurn was opened up to the outside world. This is a story which has been told elsewhere, but the coming of the military had huge implications for the Lifeboat Inn. Day-trippers no longer arrived in steam boats from Cleethorpes and Hull, but the women of Spurn were busy with other extra domestic duties. The Lifeboat Inn remained open throughout the war and did a good trade with the large number of men on the Point. James Hopper retired to Grimsby just before the war. The next licensee was William Forster, a South African. Soon after the army arrived he was apparently arrested as a spy, together with his wife, a German from Dresden, who spoke very little English. Her presence, so close to a military fort, might naturally cause unease, but both were released and William enlisted. He seems to have continued to run the pub in uniform, and was still there in 1921 according to a directory of that date. The Lifeboat Inn was still a public house in 1924, but apparently ceased trading when the War Department bought the peninsula from the Chichester-Constable family in 1925.

The former Lifeboat Inn, old cottages, the Port War Signal Station and railway shed, 1930s

The building, still a substantial one, was used as married quarters during the army's occupation during the Second World War. However its situation, so close to the River Humber, made it very vulnerable. In the 1953 East Coast floods the Humber-side end wall of the building was demolished.

The barge in front was thought to have done some of the damage, 1953

Damage done to the Lifeboat Inn during 1953 floods

Somewhat surprisingly what was now called ‘the Old Inn’, was subsequently rebuilt.

The Old Inn and cottages, 1964

The Old Inn and Port War Signal Station, 1970s

In the late 1960s and early 1970s ‘the Old Inn’ and cottages found a new role. Hull Trinity House leased one of the cottages in the lighthouse compound to Hull College of Further Education and another to the Department of Geography, Hull University, to use as field centres. At around the same time ‘the Old Inn’ over the road on the Humber side was also leased to Hull University Botany Department, so students from both institutions were well placed to study the geography, ecology and wildlife of the peninsula.

The Old Inn and cottages, 1966

By this time the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust had bought the Spurn peninsula and it had become a nature reserve. Many of the old buildings were regarded as a liability by the Trust, and so it was decided in 1978 that ‘the Old Inn’ and the lifeboat cottages (dating from 1819) should be demolished. The end of an era for Spurn pubs!

Rear of former Lifeboat Inn and old cottages, 1978

Rear of former Lifeboat Inn, 1978

Nothing remains of the pub, which must have been the scene of such jollity, drama, human activity. And now that the road to Spurn has been washed away at the northern end of the peninsula the site itself is not visited so often. A sad end.

Site of Lifeboat Inn, looking NE, 2019

Site of Lifeboat Inn, looking SW, 2019

Sign showing site of Lifeboat Inn, 2019

Acknowledgements

Many of the photos come from my own collection. The painting of the Lifeboat Inn in 1917 comes from Lily Hopper’s autograph album, and is courtesy of Jain Robinson, Lily’s grand-daughter. Rod Barratt kindly took the photos of the site in January 2019.